It is designed by Danish national treasure Arne Jacobsen, but we need to acknowledge when designs of the past are not the best solutions for a world where the idea of the ‘urban’ has changed.

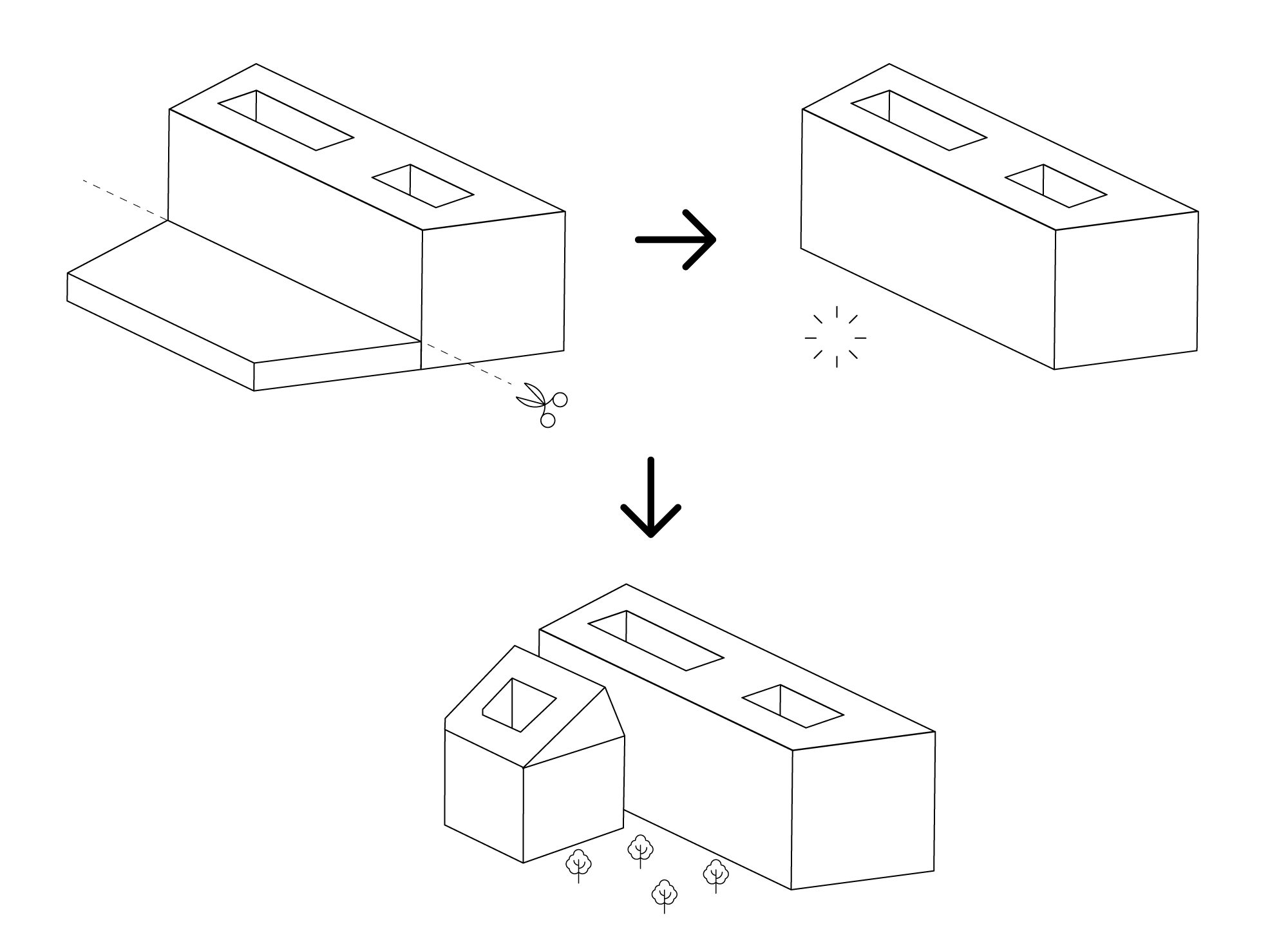

95% of the floor space in the Danish National Bank from 1978 is contained in the main, 5-storey building, while only 5% are found in the 1-storey annex that nevertheless makes up half of the building’s footprint.

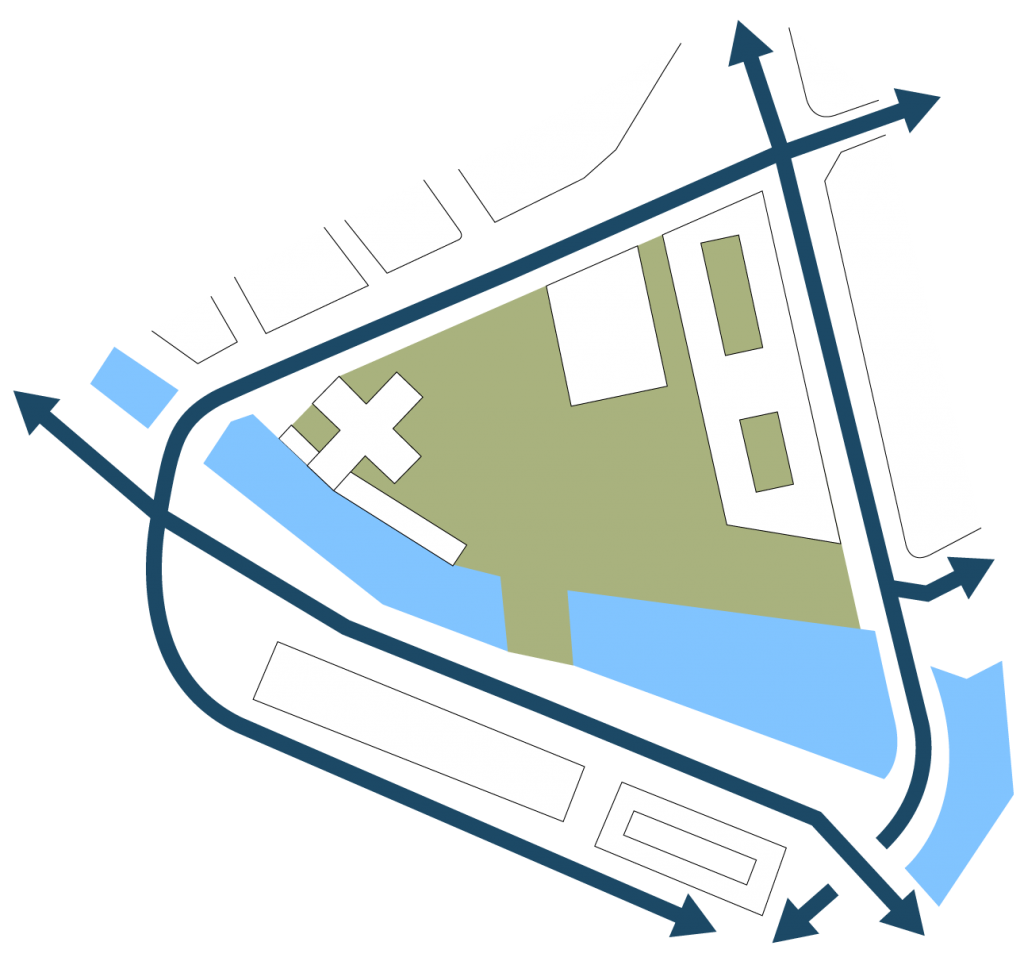

We propose removing the annex and replacing it with a new, taller building and a new, public square.

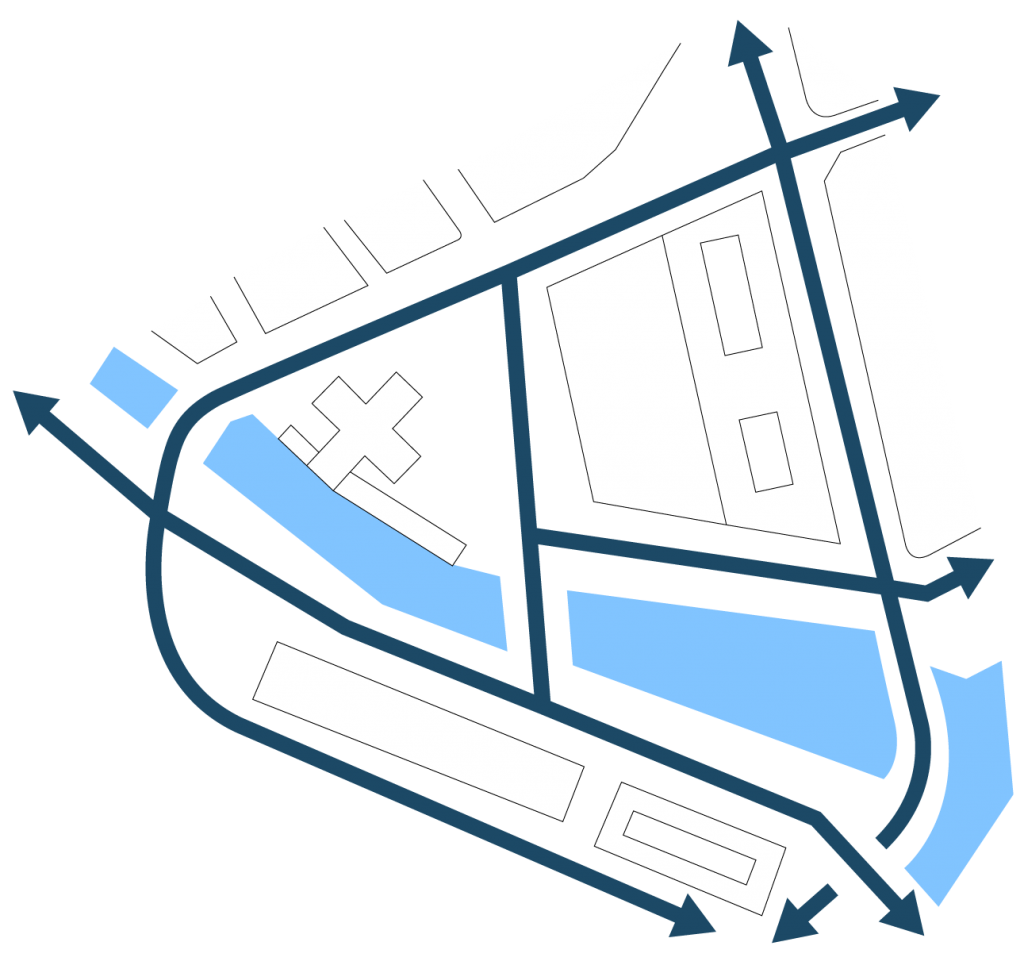

With the annex gone, half the plot can be taken over by a public square facing the canal as well as the 17th century stock exchange and the Danish parliament. The location is simply too good to be taken up by an annex for parking — as well as yet more parking between the annex and the canal.

The square will also open up a new pedestrian connection between the heart of Copenhagen’s old shopping centre and the Slotsholmen island — a connection that today feels cut off because of traffic and the large, monolithic structure you have to pass to move between the two areas.

A new building is erected on half of the plot to help define the new square, but with two other purposes:

To make way for the new bank, a historical block was demolished in the 1960s and 70s, and this has resulted in a harsh meeting between the modernist bank and it’s neighbour, a 17th century baroque church — in scale and in form.

The new building more gently slopes from one scale to another and incorporates elements from the modernist bank, such as its distinct vertical lines, into a more classical style with a clearly defined ground floor, visible roof and middle section.

However, the appearance of the building changes depending on what side you see it from — to help it create a translation between the very different styles in the surrounding space.

Lastly, the new building serves the purpose of financing the public square. Building rights for this plot of land — in one of the most premium locations in the heart of historical Copenhagen — can be exchanged for a new urban space, benefitting not just visitors and Copenhageners in general, but also the bank employees who today are “trapped” on an island isolated by car traffic.

Removing the annex will also help the main building of Arne Jacobsen’s National Bank “breathe”. Today it is surrounded by car traffic and parking on three sides, while the annex occupies the fourth.

By “freeing it” on one side, the divisive building will be allowed to be seen in a more sculptural, less obstructive, way — and having a square next to it will make it more approachable, literally and figuratively.

In short: The concept aims to create a new, urban space in a place where the city would truly benefit from it — in a way that respects the existing work, and the era it was built in, while allowing it to stand out in a way it doesn’t today.