Only a few years ago, the ‘Refshale’ island in Copenhagen was 100% industry.

Today, the shipyard has closed down, and just over half of the island has been taken over by galleries, restaurants, temporary student accommodation and more — most of it housed in the old industrial buildings.

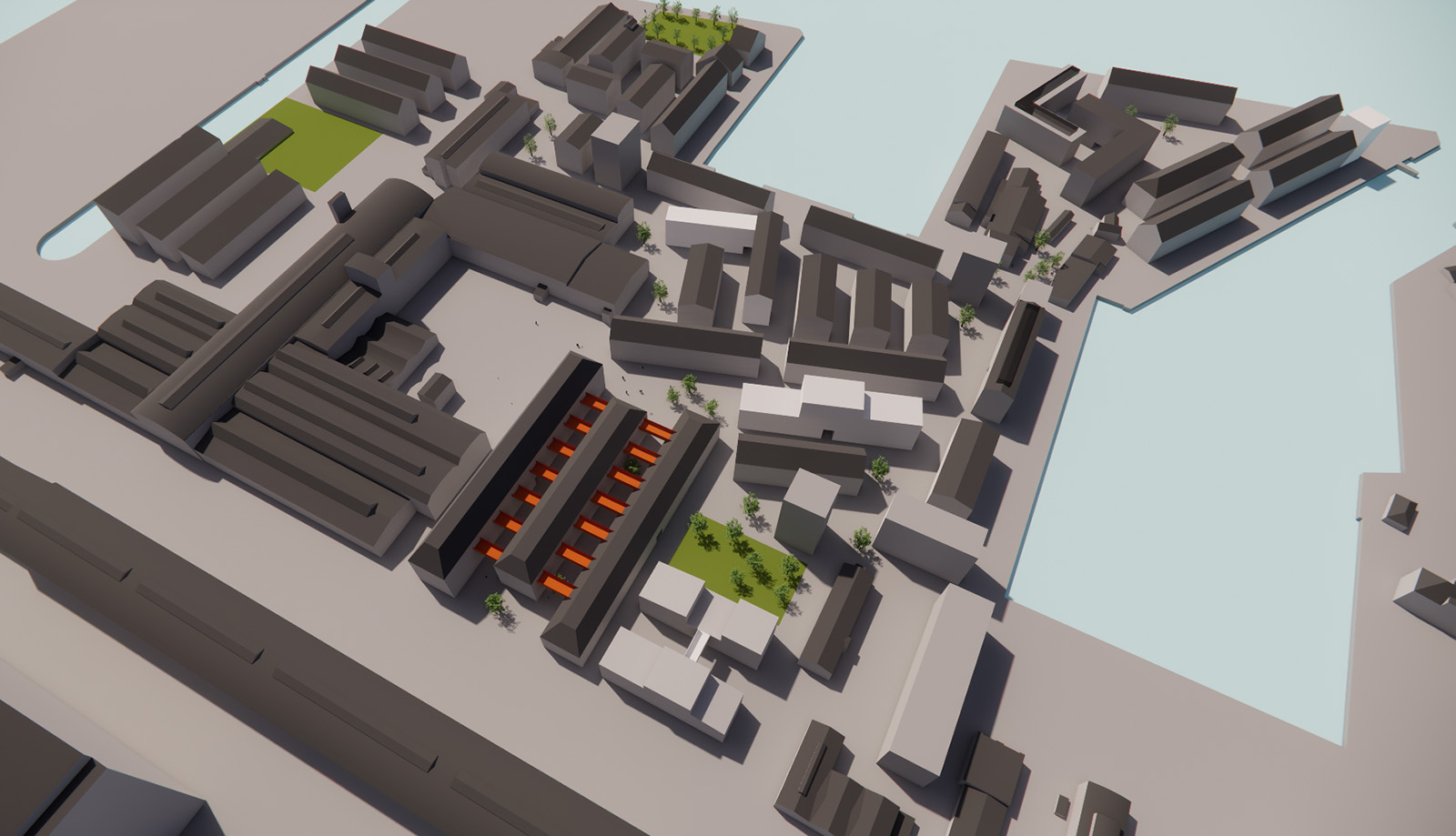

Within a few years, urban development proper will arrive, and we propose a blueprint that maintains the current character of the area, instead of erecting yet more blocks around internal courtyards, which is the traditional way to do things in Copenhagen.

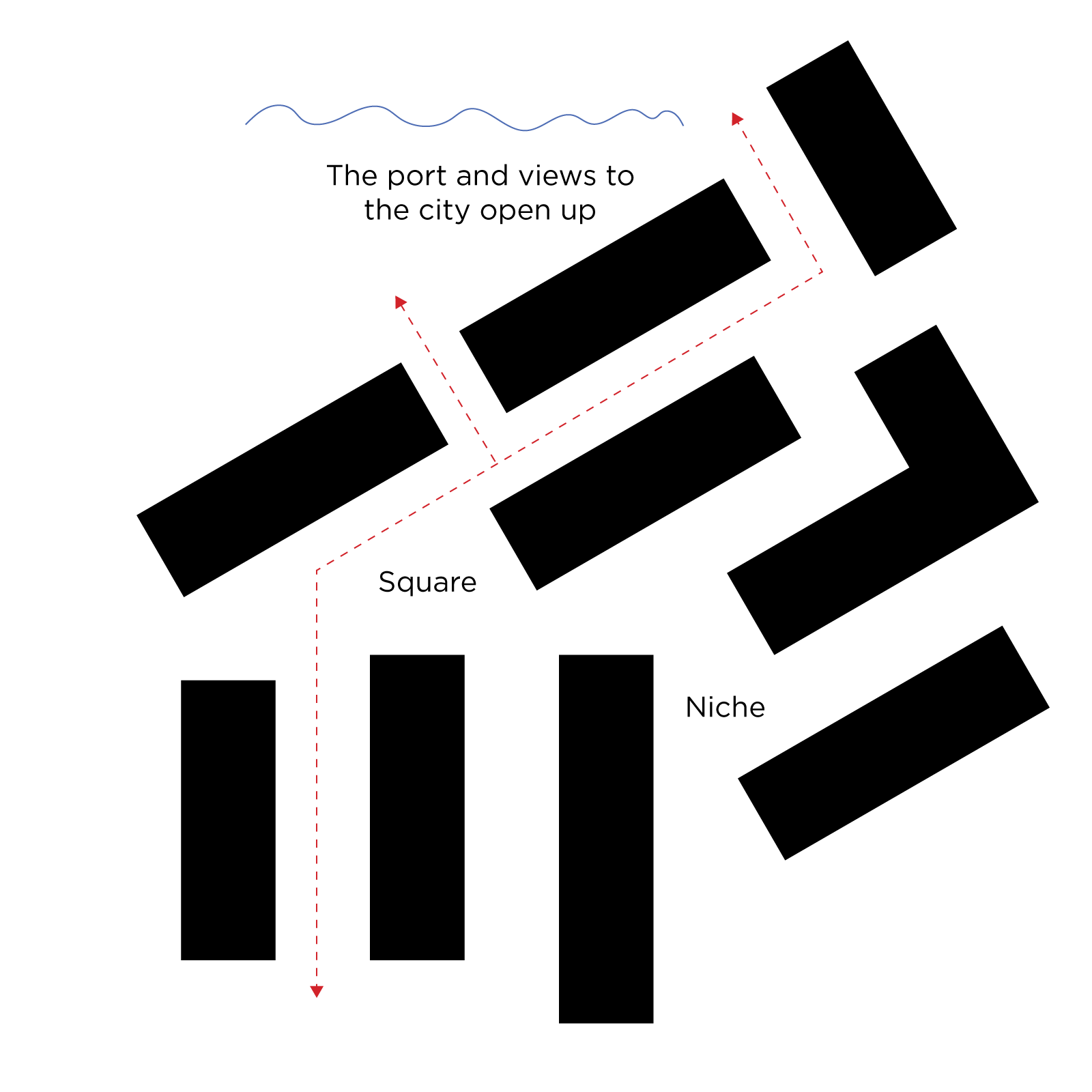

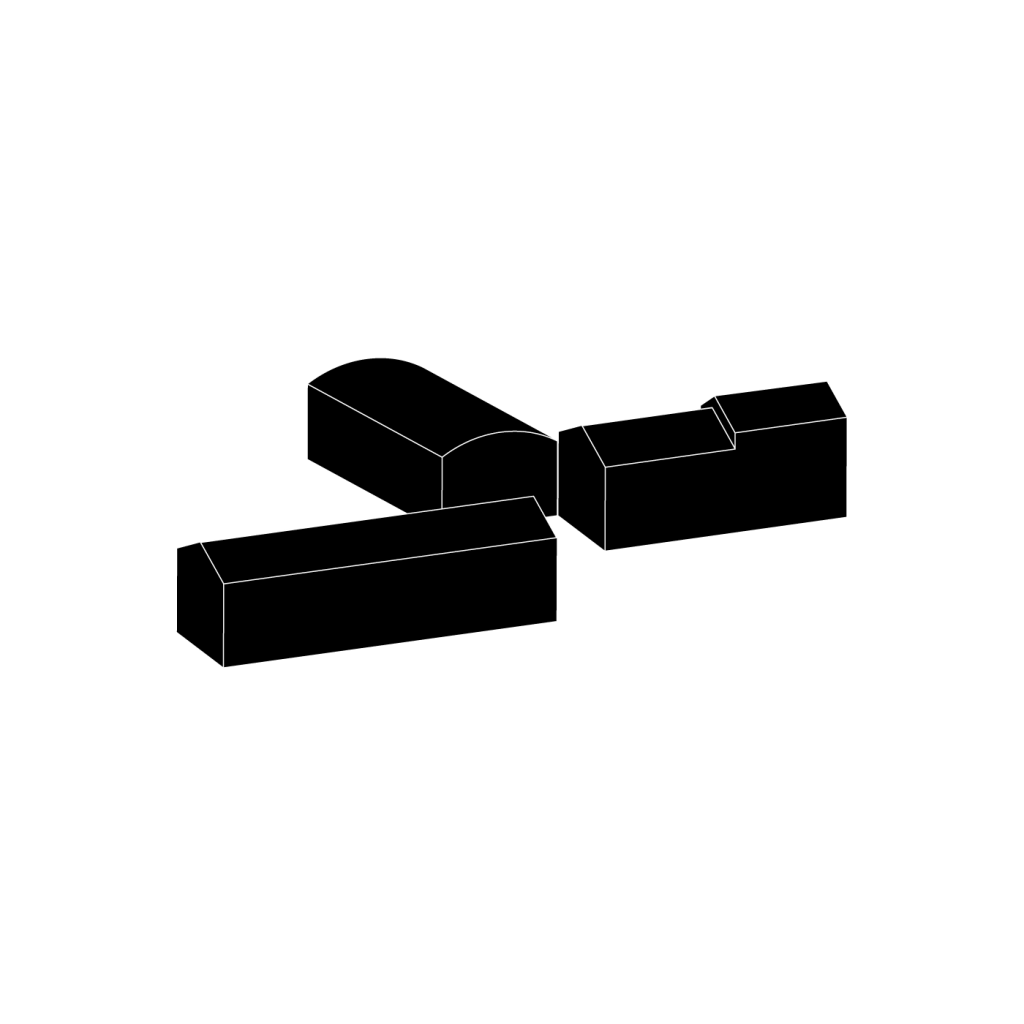

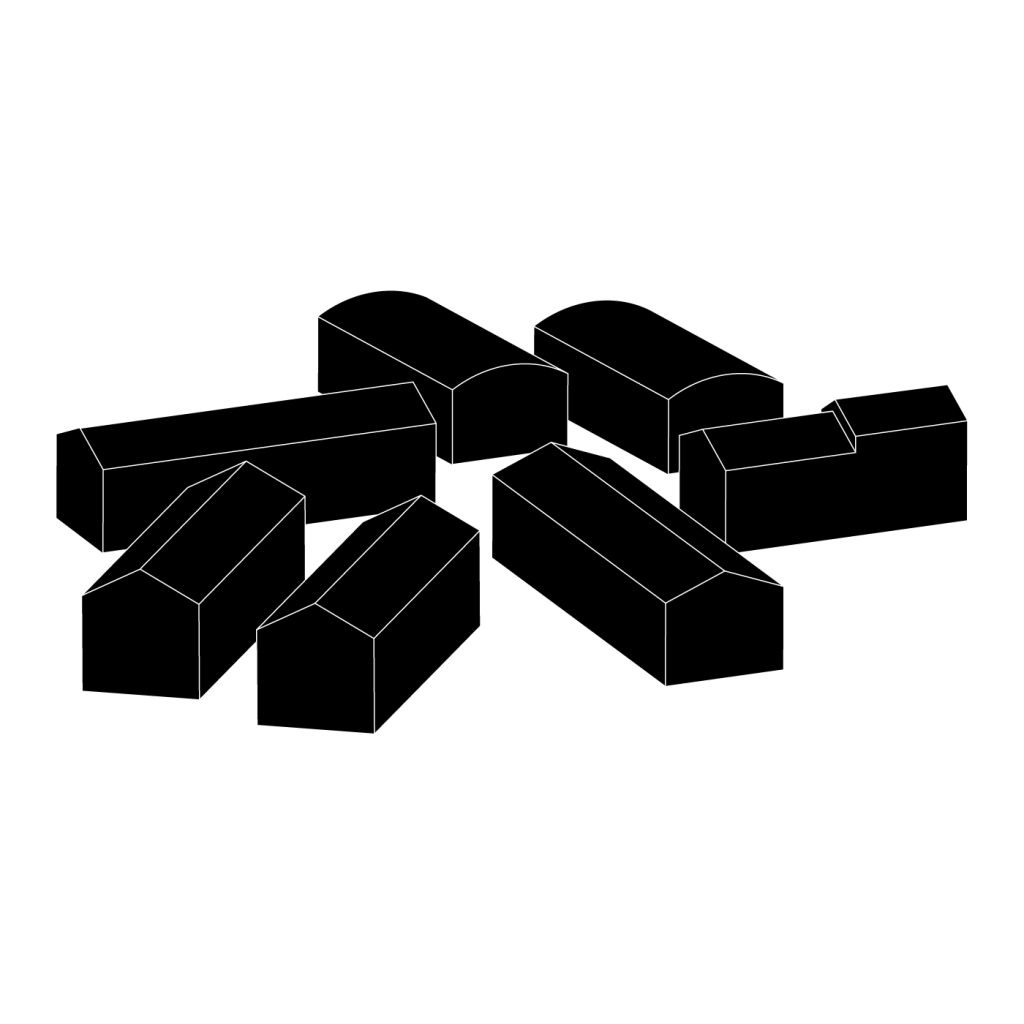

Naturally, you won’t find a single courtyard on the island today. What you will find is clusters of large, rectangular buildings, creating an unusual cityscape in Copenhagen.

This typology should become the defining characteristic when the area is planned for development — building on the island’s industrial heritage and creating an area with its own, distinct identity in the Danish capital.

By renovating the old buildings, and arranging new housing and work spaces in a similar pattern, we can expand the historic atmosphere already present:

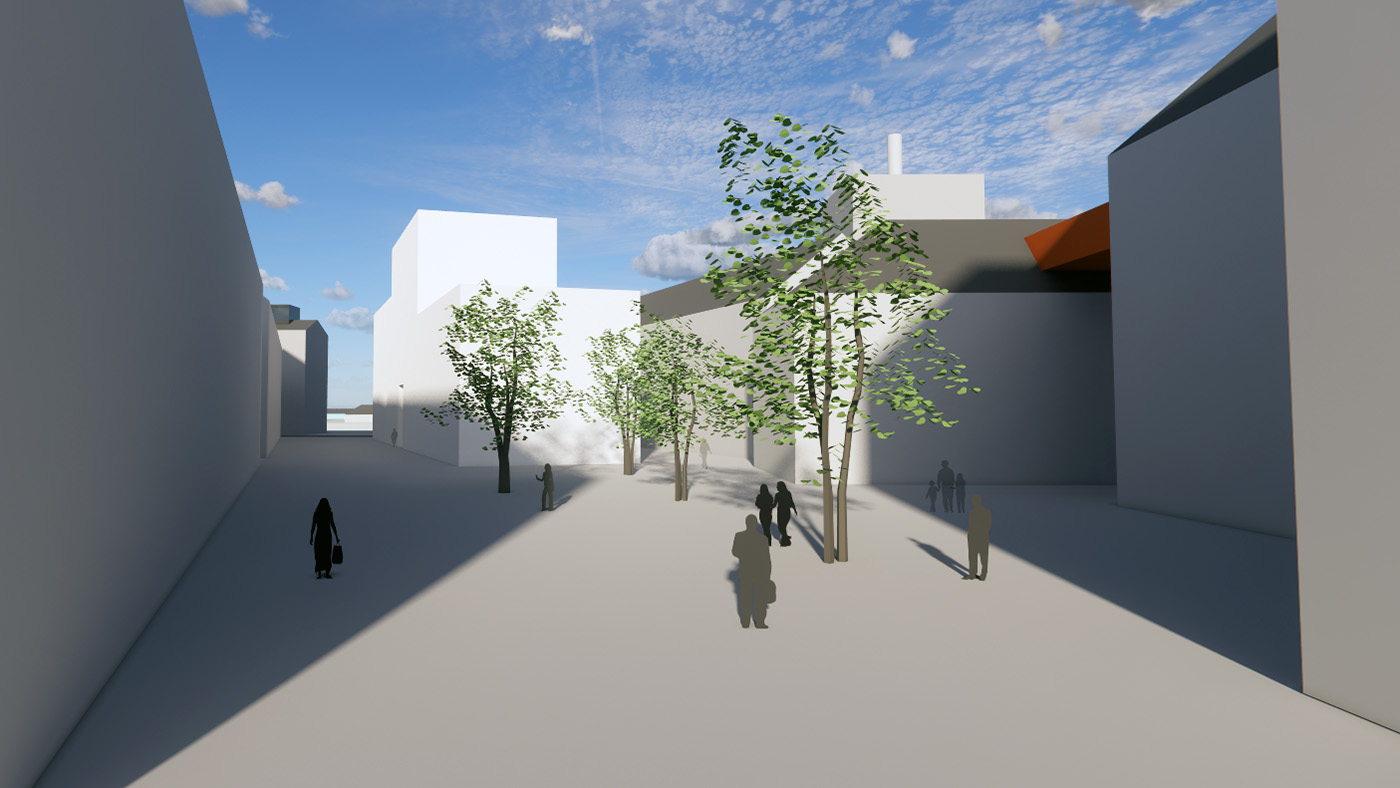

No square blocks erected in a rigid grid, but rectangular new-builds in a varied design language — that are placed in such a way that a number of very diverse urban spaces will emerge between them.

Abandoning the idea of the inner courtyard, while creating numerous green pockets between the buildings, we can also move this semi-private sphere into the shared space — opening up the neighborhood and encouraging more chance meetings and social cohesiveness.

Planning of the neighbourhood must still be rational, and car access needs to be maintained to some degree. But car access doesn’t need to mean straight, neverending streets that offer few surprises.

By adding complexity to the street plan, but allowing a few strategically placed corridors suited for cars, spaces can become better defined and more stimulating, while 4-wheeled access to all buildings is maintained.

Cycling is already a big part of Copenhagen’s transport fabric, and two metro stations and a new bridge for pedestrians and cyclists are already part of the vision for the new area.

As a consequence, car traffic can be limited to medical transportation, deliveries and other services — and to car sharing which will give residents access to cars, but without the streets and numerous car parks being required for car storage.